The Law and Me: Chinese ‘Law’ v Jennifer Zeng

(Note: This article was written for and published by Pandora's Box, 2005, Women and the world, Annual Academic Journal, Women and the Law Society, University of Queensland, Australia.)

(注:此文乃應澳洲昆士蘭大學女性與法律學會年度學術刊物《潘多拉之盒》 2005年刊所邀而寫。 )

My first memory of the ‘law’

I was fourteen before I realised my father had anything to do with the law. By that time the Great Cultural Revolution in China was over, and the public security departments, procuratorial organs and courts that had been dismantled during the Cultural Revolution were to be resurrected. As a graduate of the University of Politics and Law, my father, was recalled and given work in the new metropolitan judicial bureau of Mianyang City. He worked there before he was relocated to a remote small town for more than ten years as a ‘reactionary capitalist-roader lackey’ during the period of the Great Cultural Revolution.

I grew up in this small town, moving to Mianyang City with my father and middle sister when he was called back. But my mother and youngest sister had to remain in the town as no position was available for my mother—then a middle-school teacher who was to eventually attain the status of one of the most well-respected Intermediate Court judges there—in Mianyang. It would take more than three years for her to fight her way back to Mianyang to be reunited with my father. But not with me, as I had left that city permanently for university in Beijing—1600 km away.

At the age of fourteen, moving to a bigger city, with my father, did not look great to me. I had lost not only my mother but also a ‘home’. At that time everyone who worked for the government or state-owned factories was ‘looked after’ by the government, or the (Communist) Party more exactly, in all aspects, including being assigned a place to live. There was no such thing as buying or renting an apartment of one’s own.

The newly-established Judicial Bureau did not have an office building or any apartments for its staff. It had to rent several rooms in a motel. My father was given a bed in the male dormitory, while my sister and I had to share one bed in the female staff dormitory. As my school was too far to travel, I had to live in school on my own, only returning to the dormitory to join my father and sister on weekends and holidays.

During all of my high school days I lived a solitary existence. But little by little I did learn about the development of the Judicial Bureau of Mianyang. It was given office premises and a lawyers’ house was established under the judicial bureau so that defendants could receive legal assistance. My father was transferred to the lawyers’ house, and eventually won himself a name as one of the top ten lawyers in Sichuan Province, to which Mianyang belongs. I had heard that my father had once gained an extraordinary reputation for defeating all three lawyers representing the other side, thereby winning an almost impossible case. During the court debate the room was filled with crowds who were especially impressed by his brilliant presentations.

I was a little bit surprised to learn of his achievements—to me father was a man of few words. Actually, I never heard him talk much at home in the small town.

And I was even more surprised when he forbade me to become a ‘liberal arts’ student in the last year of my high school. In China, one year before the entrance examination for universities, every high school student has to choose whether to study ‘liberal arts’ or ‘science’. After they decide, the two groups are put into different classes.

My father explained very little of why he thought it was better for me to study science. The only reason he gave was: ‘No matter who the president of the nation is, 1+1 is always 2. You have less chance to make mistakes.’

I barely understood what he meant; but obeyed silently. I remember, back in the small town, father sometimes wrote beautiful novels, short stories and poems. But mother would always burn his manuscripts whenever she found them, sometimes before I, the only reader of my father’s work, had the chance to enjoy them. He seldom said anything when she did that, only biting his lip in a particular way which made me feel very anxious. He was doing it again when he made the comment about the president and 1+1, so I obeyed without argument, despite insistence from many people that “female minds were not designed to study science”.

The battle begins

One year later I became a geochemistry student at Peking University, one of the top tertiary institutions in China. I did exceptionally well in all my science courses with my female mind, but was constantly attracted by all the non-science stuff as well. I read all the literature and philosophies I could find in the library, and was constantly asking myself the questions asked by others for hundreds of years: ‘Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going?’ I didn’t find my answers until a dozen years later, and not before my health was totally ruined due to a medical accident I encountered during the birth of my daughter in 1992. I had two massive haemorrhages and almost died; but the blood transfusions that saved my life left me with hepatitis C—severely debilitated for more than four years.

In 1997 my parents and middle sister back in Sichuan started practicing a type of traditional qigong (Falun Gong or Falun Dafa). Its purpose is to refine the body and mind through exercise, meditation and cultivation of the heart, guided by the principles of ‘Truth, Compassion and Tolerance’. After trying it for one month, they found it wonderful and sent me a set of the books. I read them twice in one go; I was amazed to find in the books the answers to all my questions over so many years.

Right away I made the decision to commit to this practice. And sure enough, my hepatitis was found to have gone without a trace after only one month. I went back to work with renewed vitality, feeling that I was leading a new existence.

That was a golden period in my life. I held the position of manager in an investment consultant company (despite my Masters degree in science); and I regained a harmonious family life with my husband, beautiful daughter and my husband’s parents. (In China, it is accepted that the older generation will live with their child and grandchildren.)

The numbers of people peacefully practicing Falun Gong in both Beijing and my home city, Mianyang were enormous. So, by the early morning of 20 July 1999, while people slept, a plot that had been brewing for a long time finally broke. The then head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Jiang Zemin, had declared that ‘Falun Gong is competing with the Party for the masses’, realising that there were more Falun Gong practitioners (roughly 100 million) than Party members (about 60 million) in China. Thus a thorough and most ruthless crackdown was launched.

The first storm broke with the 24-hour anti-Falun Gong propaganda onslaught. Day and night, all media channels were broadcasting one thing: how evil Falun Gong was, how many people had committed suicide because it had made them mad, how the Falun Dafa Research Association was banned and how nobody was allowed to appeal through any channels. I was dumbfounded, not just by how they had fabricated these lies, but even more so by the ferociuos tone with which the bans were announced. It was all too clear that Falun Gong was to be eradicated right from the roots.

The weather was so hot, with a record high of 42.5°C. I felt suffocated, not by the heat itself, but by an extremely heavy, yet formless and invisible depravity, squeezing forcefully at me from all directions. My home instantly became a jail. Apart from being detained in a sports centre with several thousand other practitioners for a whole day on the first day of the crackdown, taken to the local police station to be interrogated, I was continually watched by my mother-in-law. She wanted to ensure that I would not practice any more, even silently behind the closed door of my small bedroom. From the ‘atmosphere’ created by the atrocious attacks in the media, every Chinese person who still had a memory of the Cultural Revolution could sense that the Party was ready to kill again. The only way out was to give it up and submit.

To give up the practice meant a return to the old days of lying in hospital endlessly, not even able to watch my daughter growing up. It would mean going back to the hopeless and helpless old days of not knowing what to do with my useless self, feeling like a prisoner impounded by my ruined health, awaiting execution.

No, I couldn’t; and I wouldn’t.

My encounter with CCP ‘justice’

The whole summer and autumn of 1999 saw me struggling everyday with my mother-in-law for my rights to practice ‘secretly’ in my little bedroom as hot as a steaming basket, while being frequently visited by my local police officer. He needed to make sure that I wouldn’t go out to make any ‘trouble’ for him.

It pained my heart so much to watch the continuous vicious attacks, and to see how frightened my in-laws were. But little by little, with the wearing-down of the initial shock, an indignation grew within me. Who gives the government the right to say that white is black and black is white? Who on earth allows the government to violate the constitution by banning a meditation practice with such peaceful and advantageous beliefs? If Falun Gong can benefit me so greatly, it can help a lot of others, and the government should encourage that benefit. And as someone who has gained from the practice and who cares about others, I should at least somehow voice my opinion.

I thought my chance came when learning that after being detained for more than five months, the four members of the Falun Dafa Research Association were to be put on trial at Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court for ‘instigating others to appeal for Falun Gong’. According to law, the longest period a person could be held in custody is one month. But because there were no legal precedents regarding how to deal with this phenomenon, and no relevant laws to go by, these members had just been locked up, awaiting the Party’s ‘policy’.

I decided to go to the court to attend the trial; firstly to make up for my regrets at never attending any court trials and witnessing how wonderful my father’s debates were, and secondly to defend the members if possible by telling the court that I was not ‘instigated’ by anyone into practicing or appealing for Falun Gong. I went to the court, but only to be arrested in the street even before I reached the front gate, together with some one thousand plus other practitioners. I was put in the detention centre right away. And this set my path to the centre another two times. At the end of the third term of a one-month detention, I was given a one-year ‘Re-education Through Forced Labour’ sentence.

My father had told me that all the lawyers in Mianyang City had been given cautioned about defending Falun Gong practitioners. In a word, no lawyer was to take up these cases under any circumstances.

I could almost see my father biting his lip again on the other end of the telephone when he told me this. And I fully understood why, as a top lawyer in the province, he never bothered to try to help me in any legal sense. No law for Falun Gong practitioners at all. They were set to be the ‘state enemy’. And the police at the detention centre even went so far as to openly declare that I was arrested because of my ‘thoughts’.

Out of my academic habit I read the labour camp sentence carefully and noticed one item saying that I could apply for a review within 60 days if I thought I had been wronged. The police ignored my request for pen and paper to write my review application. Three days later, I was sent to the ‘Re-education Through Forced Labour Despatch Division’ in Daxing County, some 20 kilometres away from the centre of Beijing.

China’s system of re-education through forced labour was set up in the 1950s to deal with the ‘remnants of the idle pre-liberation exploiting class’. Its purpose was to remould these remnants through forced labour into ‘socialist new people’. Gradually that re-education system was extended to petty and non-criminal offences like pilfering, brawling, prostitution and drug-taking. After the crackdown, it had become a major tool for persecuting Falun Gong practitioners, as no legal procedures were necessary, making it extremely ‘convenient’, and all the major provincial cities already had their own labour camps anyway.

A Gestapo-type organisation, the ‘610 office’ (named after its set-up date, June 10 1999), straddling all administrative, legal and Party organisational functions was created especially for this persecution. All labour-camp sentences were issued by the 610 office.

A year in Hell

On the first day of my arrival in the Despatch Division, I was forced to squat under the scorching sun for more than 15 hours. It sounds nothing on paper, but there were so many moments that I felt I could not last one second longer without fainting. But somehow I just wouldn’t. Both the intense and excruciating pain I felt and the crackle of electric batons applied on whoever did faint and fall, kept me vividly aware. Using all the language available in the world, let alone this, my second and far less fluent language, I would not be able to describe the suffering.

But day two was even worse. We had to stand in the small cell for sixteen hours, motionless, with our hands clasped in front of our belly and our heads lowered, looking at our feet. At the same time, we had to recite out loud the degrading labour camp regulations, espousing ‘supporting the Communist Party and socialism’; ‘not mixing with pimps and bad types’; ‘not indulging in ribald or barbarous behaviour’, and so on, and so on. I felt I would be driven mad by the humiliation of prohibitions, each one viler than the next, by the constant violation of my thoughts and the havoc this wrought on my willpower; my dispirited body being mercilessly ripped apart like a defenceless lamb.

Day three was simply a rerun of the day before. By midday I felt my head was going to burst and my nerves were shot to pieces. In a desperate attempt to break away from all this, I asked the police to give me a piece of paper to write my appeal—this was my legal right anyway.

The result was that I was dragged into the courtyard with electric shocks raining down on my body everywhere, each jolt making me tremble uncontrollably as it pierced me with a violent burning sensation. At one stage the batons stayed on me and I felt they would never be taken away.

The crackle grew in intensity—I could feel the current rippling through my body. I squeezed my eyes shut, mustering all my will against the black despair sweeping over me, and against this monstrous evil threatening to engulf me. Suddenly something snapped in my brain and I felt the whole world descend into darkness with a great roar. I collapsed, unconscious on the ground.

I don’t know how long this lasted, but as I slowly came round I found myself squatting on the ground with a criminal nicknamed Wolf. She was one of the ‘little sentries’ given police power to ‘discipline’ Falun Gong practitioners, and was trying to put my hands behind my head in the correct ‘head lowered, hands clasped’ posture required in the camp. I felt so weak that my hands slid off each time she put them up. So she just gave me a kick whenever I moved a muscle.

I squatted there, watching my sweat splashing down onto the burning concrete. Each drop shrank to nothing and evaporated without a trace within about two seconds. Soon the drops stopped, not because the sun was less fierce, but because my body had no more sweat to give.

Amidst the unbearable thirst and dizziness, I remembered father’s tightly bitten lip, and I cried weakly and soundlessly in my heart, ‘Oh father, who told you that whoever is the president of the nation, 1+1 is always 2? With Jiang Zemin in power, 1+1 could be anything!’

And that was only the third day of my labour camp career. The police told us that the only purpose for us being sent to the camp was to get us ‘reformed’ into believing that Falun Gong was evil. Further ‘reforming’ methods included sleep deprivation for up to 15 days and nights, brainwashing sessions accompanied by police equipped with electric batons; slave labour usually lasting for up to 20 hours a day, and the endless assurance that nobody could ever walk out of the camp unreformed and alive.

Beatings, electric shocks, verbal abuse, knitting sweaters for exportation until our hands bled, being bound to a bed for a continuous 50 days—all this made up our daily life in the camp. Many a time I was on the verge of total collapse; and there were many collapsing around me, from an elderly woman of 68 to a girl of 18, and from a blind woman to a paraplegic. No one who practices Falun Gongis spared.

Enough is enough—the road to ‘reform’

After several months of struggling, one day a voice cried out to me:”It’s too dark! You must get out and expose all of this to the world. You must try to stop all these inhumane crimes!’ But, how could I, unless I ‘reformed’?

After a thousand struggles which were surely more agonising than the electric shocks, I decided to do just that. The story of what was happening to thousands upon thousands of Falun Gong practitioners in Chinawould be told!

But to ‘reform’ is not an easy process. There were five steps: the writing of a guarantee; a renunciation of Falun Gong; the exposing and repudiating of Falun Gong; then going public, reading your repudiation before the whole camp, and finally helping the police torture fellow practitioners to get them ‘reformed’.

Writing my 18-page ‘exposing and repudiating’ criticism nearly killed me! Gritting my teeth tightly, I suddenly understood why my mother had burnt all my father’s writings back in that small town. Under the Communist regime, the most dangerous and unforgivable crime is somebody’s thoughts.

I was released in April 2001; but not before the hardest battle with the police to convince them that I had been really reformed by writing ‘thoughts reports’ to them again and again. And there were also the cruellest tussles between my most intense desire to leave and the deepest guilt at having betrayed my most cherished principles and having helped the police to ‘reform’ others. I felt that my integrity had fallen apart; deep within I was terrified that one day my spirit would shatter completely.

But the tragedy did not end there. I had to go into hiding only five days after I was released, no matter how I longed to be with my husband and my little daughter after more than one year’s separation. If I hadn’t, local police would have taken me to brainwashing classes, set up because labour camps alone could not hold all practitioners. My role, of course, would have been to continue to help the police to reform those held there.

Fulfilling my vows

As luck would have it, I was able to escape to Australia to seek asylum five months later. To fulfil my vows in the forced labour camp, I had finished my book, Witnessing History: one woman’s fight for freedom and Falun Gong, two years later and it was published by Allen & Unwin in March this year.

In October 2002, together with six other Falun Gong practitioners from six countries, I submitted Communications to the United Nations Committee Against Torture and the United Nations Human Rights Committee against Jiang Zemin for the persecution. This led the way for the largest human rights legal battle since World War II. Over 50 separate legal cases have been filed in more than 20 countries against the persecutors. This has not been an easy battle either. Four days after the announcement of my legal action, my husband was arrested back in China.

The legal future of human rights

Nearly three years have passed; and we have still heard nothing back from the United Nations. Here in Australia, the Supreme Court of NSW case of Australian citizen and international artist, Ms Zhang Cuiying against Jiang Zemin and the 610 Office, was allegedly interfered with by an officer in the Foreign Affairs Department of Australia, who offered to provide legal advice to the persecutor. The right to hold a banner saying ‘Stop the persecution’ outside the Chinese Embassy in Canberra is yet to be contested by Falun Gong practitioners all around Australia against Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer, who has been signing certificates every fortnight to ban Falun Gong banners and music since the day before the Chinese Foreign Affairs Minister’s visit to Australia more than three years ago.

After World War II, the judicial precedents created by the Nuremburg Court and the Tokyo Court were used only to punish the dictators who committed crimes against humanity in the name of the law. However, such punishment did not prevent dictators such as Pol Pot, Milosevic, Saddam Hussein and Kim Jong II from using autocratic state power to commit atrocious crimes against humanity and against their own people (as recorded in the ‘Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party’, published by The Epoch Times newspaper, November 2004). .

In China, a country that possesses twenty-five percent of the world’s population, autocratic state authorities continue to commit numerous crimes against humanity in various forms, but all of the judicial systems in all human society are powerless to uphold justice for these victims. The biggest crimes against humanity were all carried out in the name of state power, something that, like domestic violence on a massive scale, occurs behind closed doors.

In order to address this, a group of jurisconsults, dissidents and ordinary citizens has set up a “Special International Committee to Bring the CCP to Justice”, under the authorisation of people around the world. Its belief is that human rights are above sovereignty. Also, state sovereignty occurs only through the will of the people of that state as a whole, whilst the CCP has usurped state power through violence. There are never free elections in China. So the aim of the special committee and its associated courts is to create a set of legal principles to bring dictators to trial while they are still in a position to monopolise state power by violence.

I will again be bringing my charges against Jiang Zemin and the 610 office in the corresponding court in Sydney, under the special committee for genocide and torture. I am fully aware that this court does not have state power to back its rulings. But as Wilde once said: ‘The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it.’ The fate of humankind enters new realms through the process of continually going beyond fate and beyond the accomplished regulations.

Although I haven’t had the chance to study law because of my father’s ‘1+1 equals 2’ theory, who can say that my legal actions may not be written into human history, and perhaps even future text books for law students?

27/07/2005

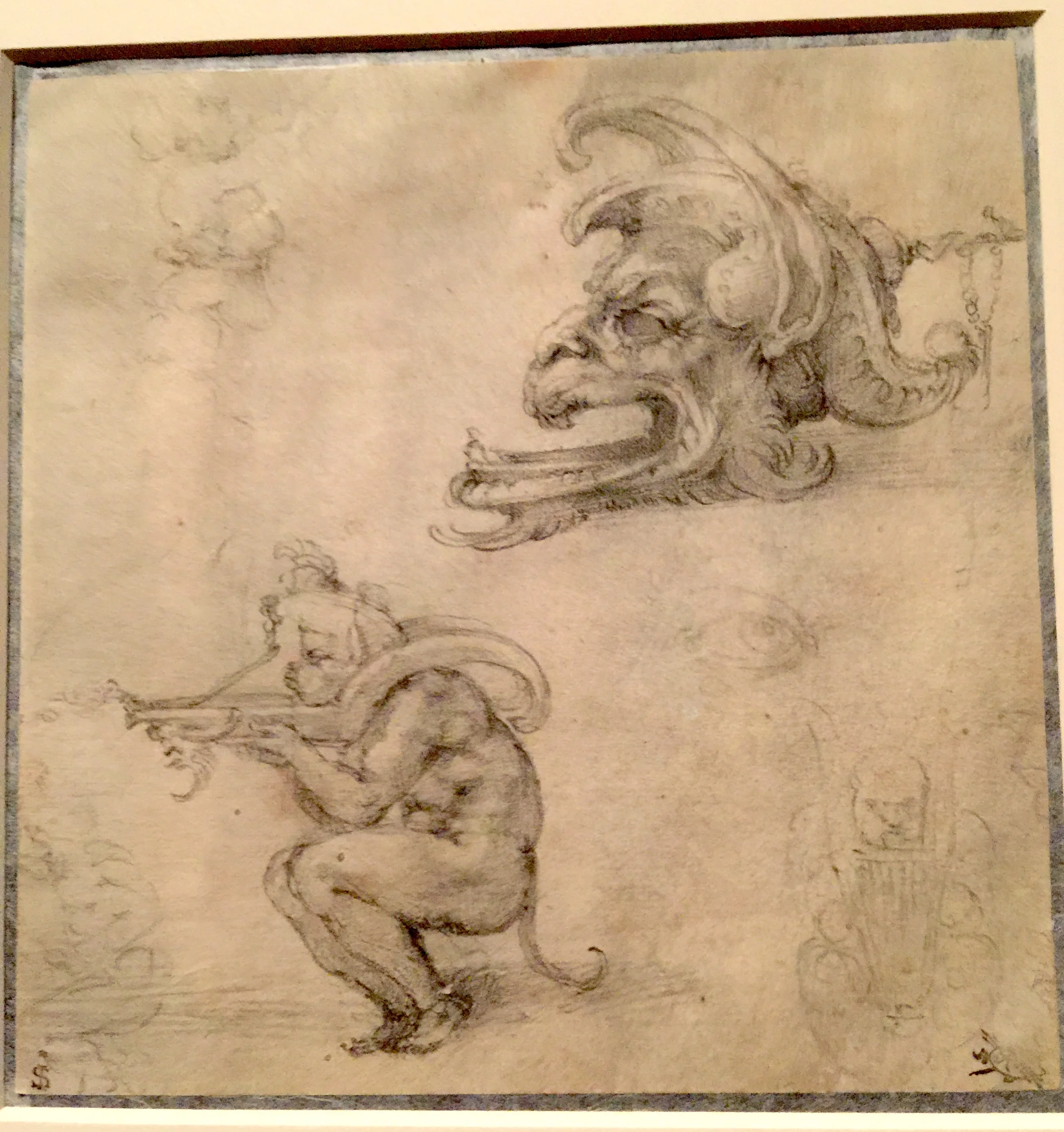

One page of "The Law and Me" inside Pandora's Box